| | |

11,500 miles of motoring through 27 States of the USA

This article appeared in Motor magazine, 25 September 1957.

Thanks to the educational activities of Mr. Noel Coward, the strange habits of Mad Dogs and Englishmen are by no means unknown to the American public. To the average American, the idea of going all the way across his vast continent by car for the fun of it, when an airliner will fly you from New York to California for $99 while you try to sleep, is a little bit eccentric, the sort of silly trip that some people make once in a lifetime. The idea of travelling any great distance in a car of European size still seems to most Americans to be even more unintelligent than driving across the continent in a real car. And as for going from New York to California in a Morris Minor, only to return again in the same car by the longest and least direct route possible "just plain nuts", we gathered, was the near-unanimous American verdict on folk who did that sort of thing.

On top of the Rocky Mountains, at the end of the second-gear climb to the 14,260 foot high summit of Mount Evans, Colorado.

As a matter of plain fact, I never did intend to make the double crossing of the North American Continent in a Morris Minor 1000. Looking for a car with long legs and a short thirst for fuel, I decided to take advantage of my opportunities as a journalist to borrow a Wolseley 1500.

Mad? If I get the chance to repeat the trip next year I shall not need asking twice

The route stretched from New York on the East Coast to Los Angeles on the West Coast and back via a large figure-of-eight across the country.

Statistically, our 11,502 miles (on a distance recorder accurate to two car-lengths in 30 miles of Turnpike) cost us $113,45 for 331.3 U.S. gallons of regular-grade petrol (starting and finishing with a full tank), an overall average of 34.7 miles per U.S. gallon equivalent to 41.7 miles per British gallon

Oil cost us $8.43 for 18 American quarts to top-up the sump, plus four changes of oil which used 3 American gallons of oil costing $6.06, together adding just under 13% to our fuel costs. Greasing at roadside garages at rather more than recommended 1,000-mile intervals cost $8, or about 7% of our petrol cost, and repairs cost us just 10 cents (eightpence halfpenny in English money) for one new tyre valve, 0.097% of our fuel cost. On the whole, we think we travelled fairly cheaply at 1.18 cents per mile (1.015 pence per mile) total motoring cost, and occasional turnpike roads at a toll of 1 1/4 cents per mile looked jolly expensive luxuries to us - we, in fact, paid out $11.55 in toll for using various bridges, tunnels and turnpikes plus $18.50 toll to take the car through Grand Canyon, Zion, Yosemite, Craters of the Moon and Yellowstone National Parks.

Will the smallest Morris cope with American conditions? Our 10 cent repair bill in 11,500 miles hints at the answer to that question. In addition to this replacement, I reset the contact breaker gap after 4,500 miles, this having closed up and made the performance sluggish by the time we reached Los Angeles. I also tightened the oil filter and oil pressure relief valve cover nuts to check slight oil leakage, adjusted the brakes after 6,000 miles to restore them after initial bedding-down, and used a Phillips screwdriver (not included in the tool kit, surprisingly) on a sun vizor bracket and the door catches to check slight rattles. Both wires had to be coupled to the stop-lamp switch when I discovered that our stoplamps were not working - I doubt if the leads had ever been coupled up previously - and at intervals I picked up the handbrake release knob from the floor and screwed it back into place, none of these quick and simple jobs involving paid help. The general view of garages which greased the Morris and could find nothing else to do to it seemed to be, that if many customers changed over from complicated Detroit automobiles to straight-forward imported models the repair trade would catch a cold ...

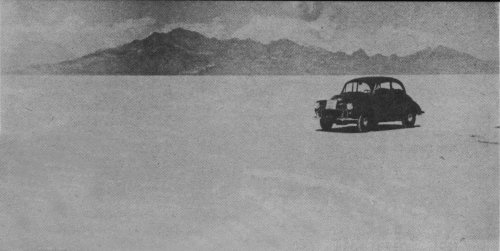

The unique product of freakish nature, the salt flats outside Wendover, Utah, look vast and lonely even when speed record attempts are in progress. The unique product of freakish nature, the salt flats outside Wendover, Utah, look vast and lonely even when speed record attempts are in progress.

Will the Minor stand heat? I think that our hottest weather was about 108°

How does a 37 b.h.p. car cope with a morning rush-hour in which every other car has upwards of 100 b.h.p. on tap? Ten days spent 20 miles out of Detroit, making daily visits to factories in and around the city showed that, with reasonably energetic use of the gear lever but not over-rewing or exceeding speed limits, the Minor got through the morning and evening rush hours quite as fast as most other folk, losing a car's length when the light first went green and the Yank alongside span its rear wheels, but usually hitting the local cruising gait of 50 m.p.h. without dropping back appreciably further. Of the European cars I saw in city traffic, a large proportion were darting from lane to lane in a manner which American cops are apt to frown upon but obviously were penetrating the traffic just as nimbly as they do in the less tidy congestion of European towns.

Down in the hot valley at Zion National Park, the Minor carries an evaporatively-cooled canvas drinking water bag in case of a puncture delay on a lonely desert road.

Will the Minor tackle big mountains? Our high spot was the summit of Mount Evans, Colorado, which at 14,260 feet claims to be the highest motor road in the Northern Hemisphere and tops the highest Alpine pass by some 5,000 feet, three of us riding to the summit non-stop without anything lower than 2nd gear being needed - we had already left our luggage at our Motel in Idaho Springs on that occasion. Even here, as on other occasions at 10,000 and 12,000 feet altitudes across the Continental Divide, the engine would still idle in a slightly ragged but quite reliable fashion, without any re-setting of the mixture. On long, straight grades up into the mountains, there were infuriating occasions when 37 b.h.p. less some loss from altitude sufficed only for perhaps 45 m.p.h. in top gear, or the pace might even sink to 35 m.p.h. in 3rd gear, what time big American cars sailed by - the occasions were infuriating because in at least 75% of the cases the cars which passed us would have to be re-passed on winding or downhill road ahead, and once re-passed might never be seen again. The "1000" engine gets across mountains quite nicely, but a "1500" engine in about the same size of car would have had advantages, both in the mountains .when altitude and gradient were adverse, and sometimes too in the plains when an adverse wind could blow all day and make our 60-65 m.p.h. cruising pace into almost a full-throttle maximum.

But, cruising at just over 60 m.p.h. most of the time, we found the little Morris well able to cover big distances. Our longest day runs were 586 miles from Montrose, Colorado to Pampa, Texas and 536 miles from Rainelle, West Virginia to New York, N.Y., both runs from late starts and including not merely ordinary meals but in each case loss of an hour due to Eastward driving across time zone boundaries. Our best accurately noted average speed away from the Turnpikes was 120 miles in a few seconds under 120 minutes without exceeding 65 m.p.h., between Ely, Nevada andWendover, Utah. In Texas, our mile-a-minute-plus cruising gait was below the local average, but there were other areas such as Kentucky where we seemed to. be the fastest car on the road - driving habits vary widely from State to In hot weather, the fact that the Minor is inclined to be draughty internally is no disadvantage, and with windows wide open the growl of a rather noisy rear axle was not conspicuous as it might be in winter.

Western landmark of the journey, Golden Gate Bridge spans an entrance to San Francisco harbour which is strangely reminicent of Falmouth Bay, in Cornwall, UK.

In New York before I started on this trip, a local motoring writer described American roads as rough.

Around American cities, the compact size of the Minor did not prove such a great advantage as the clumsiness of big cars in European cities had made me expect. At times a narrow car could filter round the corner at traffic signals when there was not room for anyone else to follow, and occasionally a short car would fit into an otherwise useless spot in an apparently full parking lot. But in the main, American cities are designed for big cars, and with kerbside parking limited to defined areas with one car per parking meter the space not occupied due to the smallness of the Morris could not be used by anyone else.

No, not lost, the Minor passes through Moscow, Michigan, going west.

It was on the open road, oddly enough, that at times we were happier in a small car than we would have been in a large one, for in many areas (Missouri seemed a typical one) quite busy roads and bridges seemed uncomfortably narrow for big cars meeting one another at speed. Crossing most of the continent from Detroit to Los Angeles with three people in the car, pack- ing all the luggage in was a job which needed to be done tidily, but for two people the Minor was big enough to permit some change of position during long drives.

Because the rear suspension has been stiffened or for some other reason, the present-day Minor does not seem to handle with quite the phenomenal precision of earlier and slower examples with side-valve engines

Sunshine was occasionally interrupted by thunderstorms, one of which flooded the main road through Otis, Colorado.

By mixing business with vacation in a manner which, apart from the irresistible temptation to add more and more visits into the programme, was highly successful, I was enabled to sample the Minor in very varied parts of America. On the first stage from New York to Detroit, a weekend got lost in the Adirondack Mountains and on the Canadian border at Niagara. Between Detroit and Los Angeles, we took in the highest mountain road and the deepest mountain canyon in the U.S.A. as well as the Mojave Desert, carrying on the front of the car the fashionable canvas "Desert Bag" of evaporatively-cooled water in case a puncture should delay us amidst the lonely, sun-scorched wastes which still await irrigation. Our route to the Salt Flats of Utah took in a Sunday run across San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge as well as more mountains. Wet weather on the salt flats gave us time off to gape at the geysers and boggle at the too-tame bears of Yellowstone.

The object of this article is not to tell readers how to make a holldaymaker's allowance of £100 cover a dollar holiday, that story must wait until the Motor Show is over. Suffice it for now that a good British small car can laugh at American road conditions, that if you can spare three weeks for holiday-making in America plus about a week each way for the transatlantic boat trip, and are prepared to sleep two to a room in comfortable but out-of-the-cities motels, you can apply for shipping accommodation in the sure knowledge that the personal and car currency allowances of £100 per person and £35 per car will not leave you too poverty-stricken a tourist to enjoy yourself in America just as much as we did.

| |